From the Congressional Glossary – Including Legislative and Budget Terms

Reapportionment / Redistricting / Gerrymander

Budget Process: A revision of a previous apportionment of budgetary resources for an appropriation or fund account. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) reapportions just as it apportions. Agencies usually submit requests for reapportionment to OMB as soon as a change becomes necessary due to changes in amounts available, program requirements, or cost factors. For exceptions, see OMB Circular No. A-11, Sec. 120, Apportionment Process (54-page PDF![]() ). This approved revision would ordinarily cover the same period, project, or activity covered in the original apportionment. (See also Allotment; Apportionment.)

). This approved revision would ordinarily cover the same period, project, or activity covered in the original apportionment. (See also Allotment; Apportionment.)

Should We Change the Size of Congress? [Article I Initiative]

Also see Apportionment (CongressionalGlossary.com) and Reapportionment and Redistricting (CongressionalGlossary.com)

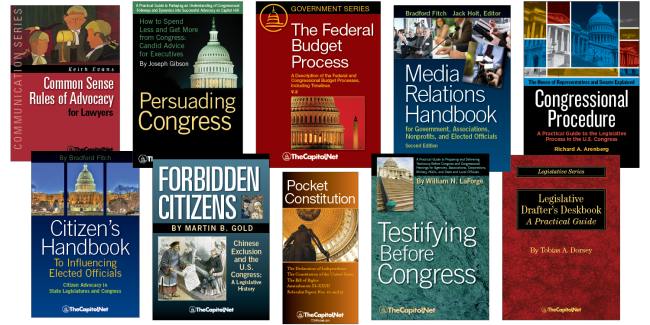

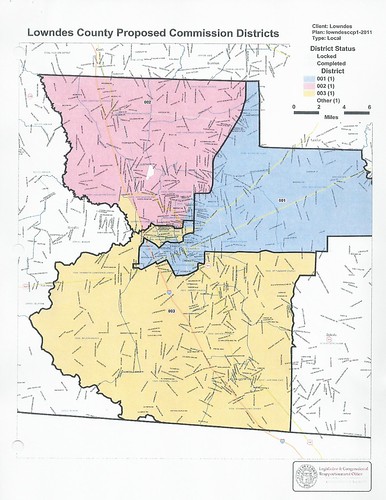

Redistricting House Districts: Using census data within the guidelines established by federal and state laws and federal and state court decisions, the states followed their own procedures to draw new congressional districts for the 2012 elections. That is the second step, following reapportionment, in determining representation in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Reapportionment is the process of distributing the 435 Congressional seats among the states after each decennial census. See “Apportionment Legislation 1890-Present” on the Census Bureau web site, and “A Note About Usage: ‘Congress’“.

The U.S. Census and the Amazing Apportionment Machine

Every ten years, an additional election pressure is added for incumbent candidates for House seats. As required by the Constitution, a census is taken, and seats in the House are then reapportioned by law among the states, based on each state’s population relative to all other states. After the House seats are reapportioned, state legislatures, commissions created by state law, or state or federal courts take over and redraw congressional district boundaries. Subject to federal and state laws and court decisions, including Supreme Court decisions, the body doing the redistricting tries to obtain an equal population in each district in a state. Redistricting goals might include favoring a political party in some of the districts, or trying to accomplish other purposes, such as the creation of districts with a majority of minority population or with geographical compactness. Court cases are used to challenge districting decisions, and several states have redistricted or considered redistricting during a decade.

Understanding Redistricting

In most states, the legislatures enact redistricting plans, which are then submitted to the governor for approval or veto. Other states use commissions to create redistricting plans. In some states, failure by the legislature to act can send responsibility for redistricting to a commission.

Although laws and court decisions govern redistricting decisions, redistricting is a political process. It is particularly painful to congressional incumbents in states that have lost seats. Unless one or more incumbents retire, two incumbents are likely to face each other in a primary if they are of the same party, or in a general election if they are of opposing parties. However, redistricting is also viewed as an opportunity by Democrats and Republicans to strengthen their respective party’s representation in Congress. A party might attempt to add its party’s voters to a marginal district to shore up its strength in that district, or it might add its party’s voters to a district that has favored the other party’s candidates in an attempt to destabilize the district’s voting pattern. The parties might make a deal to create districts favorable to each party or to favor each party’s incumbents.

Even in states that gain seats, redistricting can be a problem for incumbents. Where a party controls both houses of the legislature and the governorship, it often uses this power to increase the likelihood of winning additional districts, both existing, albeit revised, and new. In states with commission redistricting, there can be a sense of unpredictability and lack of influence by politicians over the outcome. And, the addition of districts due to reapportionment offers additional opportunities for drafting district lines to favor a party, a racial or ethnic group, a socioeconomic group, or another set of voters.

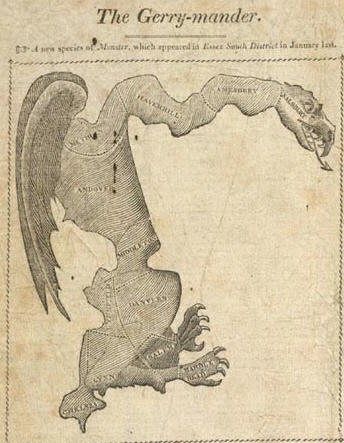

Gerrymander

Rearranging district lines to assure one political party an advantage in upcoming elections.

In 1812, Jeffersonian Republicans forced through the Massachusetts legislature a bill rearranging district lines to assure them an advantage in the upcoming senatorial elections. Although Governor Elbridge Gerry had only reluctantly signed the law, a Federalist editor is said to have exclaimed upon seeing the new district lines, “Salamander! Call it a Gerrymander.” This cartoon-map first appeared in the Boston Gazette for March 26, 1812.

“Elbridge Gerry and the Monstrous Gerrymander,” by Jennifer Davis, Library of Congress, February 10, 2017

Gerrymandering: Crash Course Government and Politics #37

Also see Apportionment; District; Mid-Term Election.

More

- Apportionment (CongressionalGlossary.com)

- Reapportionment and Redistricting (CongressionalGlossary.com)

- “The seven stages of the office seeker“

- Apportionment (politics) – Wikipedia

- “Attention, America: We’ve All Been Saying Gerrymander Wrong,” by Reid J. Epstein and

Madeline Marshall, Wall Street Journal, May 24, 2018 - “Partisan Gerrymandering: Another Supreme Court Showdown?” by Walter Olson, CATO, August 28, 2018

- OMB Circular No. A-11, Sec. 120, Apportionment Process, 2017 (54-page PDF

)

) - Reapportionment – Google News

- “The House of Representatives Apportionment Formula,” CRS Report RL31074 (31-page PDF

)

) - “House Apportionment 2000,” CRS Report RS20768 (8-page PDF

)

) - “The House of Representatives Apportionment Formula: An Analysis of Proposals for Change and Their Impact on States,” CRS Report R41382 (33-page PDF

)

) - “House Apportionment,” CRS Report RS21638 (8-page PDF

)

) - Apportionment and Redistricting Following the 2020 Census,” CRS Insight IN11360 (6-page PDF

)

) - “Congressional Redistricting 2021: Legal Framework,” CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10639 (8-page PDF

)

) - “Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives,” CRS Report R45951 (36-page PDF

)

) - “Redistricting Commissions for Congressional Districts,” CRS Insight IN11053 (6-page PDF

)

) - “Congressional Redistricting Criteria and Considerations,” CRS Insight IN11618 (5-page PDF

)

)

Courses

- Congressional Operations Briefing – Capitol Hill Workshop

- Drafting Federal Legislation and Amendments

- Writing for Government and Business: Critical Thinking and Writing

- Custom Training

- Drafting Effective Federal Legislation and Amendments in a Nutshell, Audio Course on CD

- Congress, the Legislative Process, and the Fundamentals of Lawmaking Series, a Nine-Course series on CD

Publications

Legislative Drafter’s Deskbook: A Practical Guide

Pocket Constitution

Citizen’s Handbook to Influencing Elected Officials: A Guide for Citizen Lobbyists and Grassroots Advocates

Congressional Procedure

CongressionalGlossary.com, from TheCapitol.Net

For more than 40 years, TheCapitol.Net and its predecessor, Congressional Quarterly Executive Conferences, have been teaching professionals from government, military, business, and NGOs about the dynamics and operations of the legislative and executive branches and how to work with them.

Our custom on-site and online training, publications, and audio courses include congressional operations, legislative and budget process, communication and advocacy, media and public relations, testifying before Congress, research skills, legislative drafting, critical thinking and writing, and more.

TheCapitol.Net is on the GSA Schedule, MAS, for custom on-site and online training. GSA Contract GS02F0192X

TheCapitol.Net is now owned by the Sunwater Institute.

Teaching how Washington and Congress work ™