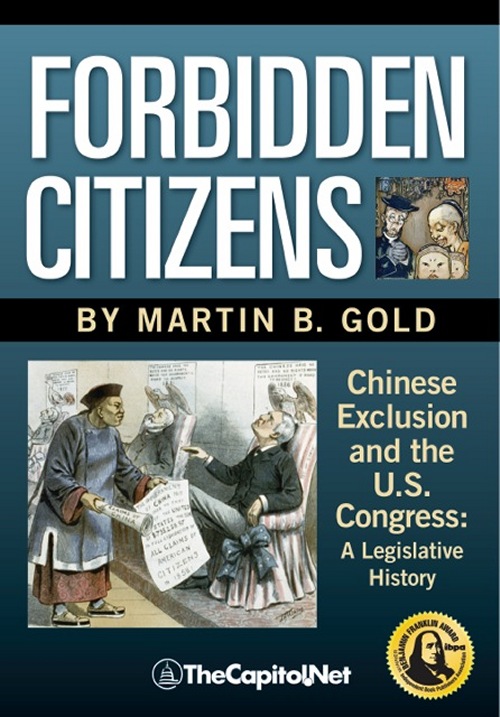

Forbidden Citizens

Chinese Exclusion and the U.S. Congress: A Legislative History

By Martin B. Gold

Forbidden Citizens: Chinese Exclusion and the U.S. Congress

Described as “one of the most vulgar forms of barbarism,” by Rep. John Kasson (R-IA) in 1882, a series of laws passed by the United States Congress between 1879 and 1943 resulted in prohibiting the Chinese as a people from becoming U.S. citizens. Forbidden Citizens recounts this long and shameful legislative history.

See preview on Google Books

Additional Resources

— Related Books

— Political Cartoons

— People and Internet Resources

— Timelines

In 1907, immigration to the United States peaked at more than 1,285,000 (mostly European) immigrants. At twenty years old, my grandfather came to New York from Tsarist Russia the next year. Speaking no English, he went to night school for language study. He found work in the garment industry, eventually owning his own business. Escaping religious persecution in the old country, he cherished American freedom. As soon as he was eligible, he became an American citizen. For the remainder of his life, America was not merely his home but his passion.

These opportunities were open to my grandfather because he was a European. Had he been Chinese, he almost surely would have been barred from entering the United States. And if, by a quirk, he had been admitted, he could not have gotten U.S. citizenship.

Immigrants have traditionally encountered social and economic obstacles as they seek to find a place in a new society. But the United States Congress subjected the Chinese to unique legal impediments aimed squarely and solely at them. Between 1879 and 1904, a time when immigration from Europe was wide open, Congress passed nine major Chinese exclusion bills. Two were vetoed, but seven became law. Anti-Chinese provisions were placed in other laws as well, such as those involving the annexation of Hawaii and the Philippines. When Congress finally repealed this immense body of legislation in 1943, fourteen statutes were affected.

The most notorious of these laws was popularly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But the Act was no isolated measure passed by Congress in a weak or misguided moment. Controversial when first proposed, Chinese exclusion rapidly became consensual–and Congress continued to tighten the policy.

These laws not only involved exclusion from immigration; they also outlawed Chinese citizenship, even for those who had arrived legally before the gate was closed in 1882. Once Congress forbade naturalization, the Chinese were exposed to repeated discrimination with no political recourse. Until the 1943 repeal, no Chinese born outside of the United States could become an American citizen.

It appeared simple to single out the Chinese for this treatment. Compared to Europeans, they were different in appearance, clothing, language, diet, religion, and social structure. Insisting that the Chinese could not assimilate into American culture, lawmakers simply would not permit them to do so. While pandering for votes, especially in the Pacific region, Democrats and Republicans alike found the Chinese easy prey.

Not that the political targeting of Chinese immigrants went unchallenged in Congress. Heroes were occasionally found on Capitol Hill. Great Senators such as Charles Sumner, Hannibal Hamlin, and George Hoar stood against exclusion. Representative William Rice was a leading opponent and Representatives Warren Magnuson and Walter Judd led efforts for repeal. But until 1943, opponents of exclusion were outvoted and, with each successive debate, their numbers dwindled.

Using senators’ and representatives’ own words, this book chronicles the sad and disturbing legislative history of the Chinese exclusion laws, with many passages transcribed from the actual debates. The appalling racism that permeated Congress becomes all too clear. Unfortunately, these vicious remarks were neither isolated nor atypical.

Members of Congress are quoted extensively. Even allowing for differences of expression over decades, the race prejudice in these debates is vivid. It is difficult to imagine that the exclusion bills could have been passed, even back then, if members of Congress had not ostracized the Chinese from the rest of American society.

The first piece of broadly anti-Chinese legislation to pass was the Fifteen Passenger Bill of 1879, described in Chapter Two, which President Rutherford B. Hayes vetoed.

However, the story really begins with the 1870 debate over naturalization rights, set out in Chapter One. But for a Senate filibuster led by Nevada’s William Stewart, legislation very likely would have passed to grant legal Chinese immigrants a path to citizenship. As Stewart himself later proclaimed, had the Chinese become voters, there would have been no exclusion policy.

Chapters Three through Ten discuss exclusion debates from 1882 through 1904. Chapter Eleven is about the passage of repeal legislation in 1943.

During this period, China was in a state of continuous upheaval. The Qing Dynasty, which had ruled China from 1644, was disintegrating. When it attempted to stop the import of opium into China by the British East India Company, the Qing suffered a defeat at British hands in the First Opium War (1839-1842) and then retreated in the face of ongoing Western interference.

Domestic unrest in China during this period was also rife. The Manchu Qing Dynasty was weakened by the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), as well as by the Boxer Rebellion (1900).

In these years, China was poor, backward, and generally unstable. As Congress implemented Chinese-American treaties, or legislated around them, it did not pay China’s wishes much heed. The Dynasty was finally overthrown by the republican revolution movement late in 1911.

Established on January 1, 1912, the Republic of China, led by the Nationalist Party (Guomingdang, also Kuomintang, or KMT) attempted to modernize and unify the country. However, the republic was beset first by conflicts with local warlords and then by a Communist insurgency. While conflict between the Nationalists and Communists raged, Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931, and, in 1937, launched a general Sino-Japanese war that lasted until 1945.

The United States entered the Pacific war in 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. China and America allied to oppose a common Japanese enemy. Repeal of the exclusion laws in 1943 was a war measure, undertaken by President Franklin Roosevelt and Congress to bolster America’s Chinese ally.

The exclusion story is unfamiliar to most Americans, especially those not of Asian heritage. Freed from the burdens of these unjust laws, Chinese-Americans have prospered in the United States. A people Congress claimed couldn’t assimilate have assimilated so well that it’s hard to find the evidence of past discrimination against Chinese in America.

Chinese-Americans have been leaders in business, the professions, sports, and the performing arts. And they’ve worked in the top ranks of American government. In the executive branch, Elaine Chao broke ground, serving as secretary of labor (2001-2009) for President George W. Bush. Gary Locke was the first Chinese-American to be chief executive of an American state, as the twenty-first Governor of Washington (1997-2005). Locke later served as secretary of commerce and then Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China. Senator Hiram Fong (R-HI), a senator from 1959 to 1977, was the pioneering Chinese-American on Capitol Hill. Elected in 2009, Representative Judy Chu (D-CA) is the first Chinese-American woman to serve in either chamber of Congress.

Such success stories notwithstanding, the experience of early Chinese immigrants was uncommonly difficult because of legal discrimination against Chinese. The distress Congress caused for multiple generations of Chinese–those who were directly affected as well as their families–is still real. Shedding light on the past helps to ensure that such miscarriages do not recur.

Forbidden Citizens is available in both hardbound and softcover editions, and an ebook.

2012, 616 pages

LCCN: 2011943122

Softcover, $29.95

ISBN 13: 978-1-58733-257-9

1587332574

Dimensions: 6.69 x 9.61 x 1.2

Weight: 2 pounds

Buy softcover from TheCapitol.Net

Buy softcover from Bookshop

Buy softcover from Amazon

Buy softcover from Barnes & Noble

Hardbound, $38.95

ISBN 13: 978-1-58733-235-7

1587332353

Dimensions: 6.69 x 9.61 x 1.3

Weight: 2.5 pounds

Buy hardbound from TheCapitol.Net

Buy hardbound from Bookshop

Buy hardbound from Amazon

Buy hardbound from Barnes & Noble

Ebook $9.95

EISBN: 9781587332593

Buy ebook from Google

TheCapitol.Net is a non-partisan firm, and the opinions of its faculty, authors, clients and the owners and operators of its vendors are their own and do not represent those of TheCapitol.Net.

www.TheCapitol.Net/Publications/ForbiddenCitizens.html

TCNCEA.com

ForbiddenCitizens.com

ForbiddenCitizen.com

For more than 40 years, TheCapitol.Net and its predecessor, Congressional Quarterly Executive Conferences, have been teaching professionals from government, military, business, and NGOs about the dynamics and operations of the legislative and executive branches and how to work with them.

Our custom on-site and online training, publications, and audio courses include congressional operations, legislative and budget process, communication and advocacy, media and public relations, testifying before Congress, research skills, legislative drafting, critical thinking and writing, and more.

TheCapitol.Net is on the GSA Schedule, MAS, for custom on-site and online training. GSA Contract GS02F0192X

TheCapitol.Net is now owned by the Sunwater Institute.

Teaching how Washington and Congress work ™